Questions about the 2014 Iranian 'Psychedelic Fatwā' and Wahid Azal? A 3 Part Series

Part 1: The ‘Psychedelic Fatwā

Part 1: The ‘Psychedelic Fatwā

In 2014, stories began to circulate about the release of an Islamic fatwā, a non-binding religious ruling or legal opinion on a point of Islamic law issued by a qualified Islamic scholar, that allegedly signalled the ‘permission’ to use psychedelic substances. It created a host of headlines and stories such as, Psychedelics Now Halal In Islam ; Iranian religious authority considers psychedelic medicines Halāl ; You Won’t Believe Which Middle East Theocracy Takes an Enlightened Line on Entheogens and Psychedelics! , and more. The stories were all generated from a single source, no mainstream release of any sort of fatwā. took place in Iran, or anywhere, and all accounts pointed to a rather controversial individual who goes by the name Wahid Azal, who, as we shall see, has been known to make some other notable outlandish claims.

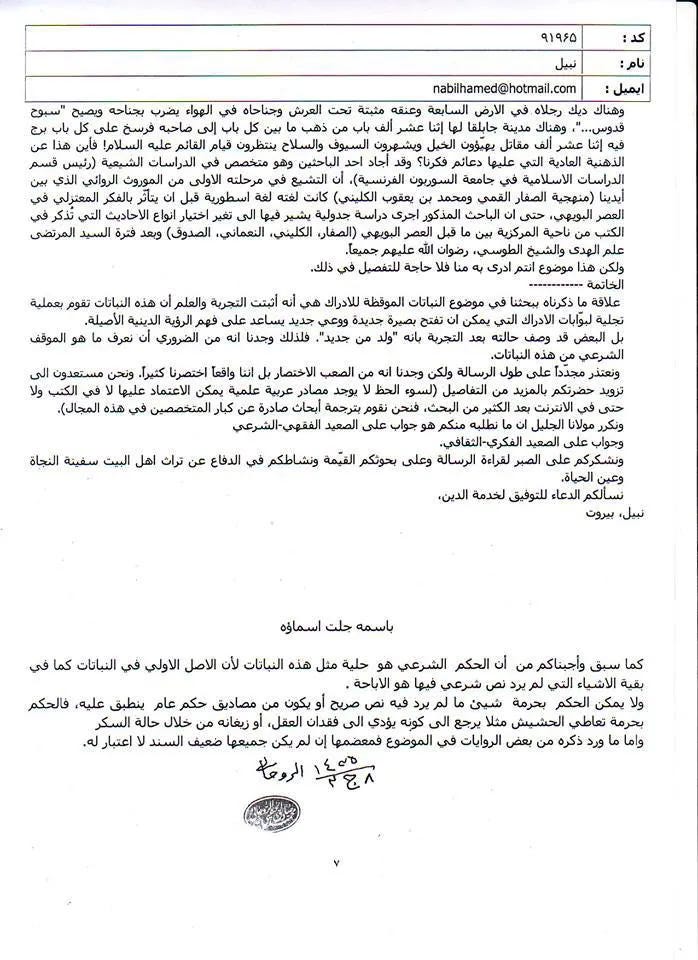

Ayatollah Rohani’s alleged 2014 ‘Psychedelic Fatwā.

This is the whole fatwā, according to Wahid Azal’s translation, any talk of psychedelic substances is in the alleged correspondence to Ayatollah Rohani, not from Rohani himself. This came after a correspondence that allegedly included excerpt from various books, academic papers and online resources relating to psychedelics, according to Azal’s account:

In His Name, Glorified are His Names

As we have previously answered you: the religious ruling concerning such plants is permissibility (ḥilliyya), for the default principle with plants—as with all other things for which there is no specific revealed text—is permissibility. One cannot judge something to be forbidden unless there is an explicit text to that effect, or unless it clearly falls under the application of a general prohibition.

The ruling that hashish (for example) is forbidden is due to the fact that it leads to loss of intellect or to stupefaction through a state of intoxication.

As for what has been cited from certain reports on this topic, when examined all of them have weak chains and are not to be considered authentic.

Signature: Ayatollah Muhammad-Sadiq Rohani

Basically, what Ayatollah Rohani is saying, is there is no reference in the Koran specifically banning these substances by name or references to them at all. But in regards to the information that Wahid and his colleagues sent in, the Ayatollah Rohani states “As for what has been cited from certain reports on this topic, when examined all of them have weak chains and are not to be considered authentic”. The rest of the correspondence has never been published. What he seems to be referring to “reports” here as “weak chains” is the copious amount of data that according to Wahid, in his Reality Sandwich interview, was sent to the Ayatollah in the correspondence.

During the course of the eighteen month dialogue, not a stone was left unturned by the Grand Ayatollah and his interlocutors, and he asked countless very pointed and precise questions, and in turn he was answered very precisely and with copious quotations, citations, clarifications and elaborations provided to him from Western academic source material (which were all very carefully translated for him into Arabic). These included Benny Shanon’s The Antipodes of the Mind (Oxford: 2002) as well as numerous articles from MAPS, selections from various other academic monographs, assorted published and unpublished anecdotal material, not to mention a plethora of online sources. To the best of our determination, during the course of this correspondence, the Grand Ayatollah became quite well acquainted with the issues involved, and in as much detail as could be given him during that time frame. Medical, pharmacological, neurological, ethnobotanical, legal, scriptural, theological, philosophical and, as mentioned, visionary (so esoteric and noetic) topics were all broached with him one by one, and in depth, so his final decision as a high Shi’i Muslim cleric and jurisprudent was as the result of a sound and well-informed overall grounding on most facets of the question.

Unfortunately, this full correspondence has. not been published. On Wahid’s s Academia account he lists the paper, “The Iranian Shiʿi seminary (hawza) assents: Entheogenic Shiʿi Islam and Grand Ayatollah Rohani’s March 2014 fatwā in context” and description With a link to a video panel discussion. :

Following an eighteen month email dialogue commencing in late 2012, in March 2014 Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Sadeq Hussaini Rohani -- one of the eminent Iranian religious sources of emulation (marjaʿ taqlīd) of Qom, Iran -- issued a fatwā (ruling) determining that the use of entheogenic plants and substances under the guidance of qualified experts is permissible (ḥalāl) for Twelver Shiʿi Muslims and therefore not forbidden (ḥarām) by the sharīʿa. This talk will briefly discuss the historical context and theoretical underpinnings which made such a momentous jurisprudential ruling from the seat of Iranian orthodoxy possible. It will offer a short biography of this leading dissident Iranian cleric himself, and also touch upon the pervasive presence of entheogenic plants and substances within Iranian culture and spirituality as far back as ancient antiquity.

However when you go to access the paper you get “N. Wahid Azal hasn’t uploaded this talk.” The video offers but a brief description, and is no way to verify what was said specifically in the correspondence by Ayatollah Rohani without at least excerpts. When pressed for the original Persian scan, Wahid is said to reply that it’s private correspondence.

In the video, Wahid makes the following claim about the fatwā at 20:20 :

Grand Ayatollah Rouhani issued a formal decree a fatwa stating that from the point of view of faith or the or the theoretical side of Sharia as far as Shia Muslims are concerned and as far as his understanding as a Grand Ayatollah and source of Emulation that it is considered Halal, permissible, for Shia Muslims to use and utilize plant psychoactive substances provided it is under the supervision of qualified experts leaving that aspect vague as to what that actually means and also that these plant substances do not harm whether physically or mentally so long as these caveats these precautions are observed that as far as he’s concerned there is really nothing that can allow a Shia Muslim jurist at least to rule these illicit and impermissible in Shia Islam. (Wahid Azal, 2014)

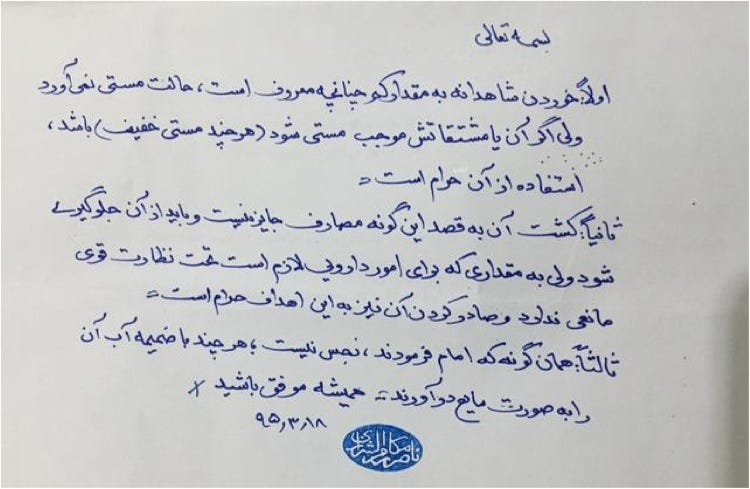

The only part of the said correspondence regarding psychedelics that has been published in regards to the fatwā states the following:

The connection between what we have mentioned and our research topic—plants that awaken perception—is that experience and science have shown these plants carry out a purification of the gates of perception, which can open a new insight that helps in understanding original religious vision. This is not a defect; rather, after trying them some describe the state as a “return.”

For that reason, we have found it necessary to know what the proper religious-legal position on these plants is.

We apologize again for the length of the letter; yet we also found it hard to be brief, for we have condensed a great deal. We stand ready to supply you with further details and Arabic sources, although—unfortunately—few reliable Arabic academic sources exist that can be relied on in books, whereas on the internet there is a great deal of research, but in English. We can provide translations of studies issued by leading specialists in this field.

We repeat, our noble master, that what we are asking from you is an answer on the jurisprudential-legal plane, and an answer on the intellectual-cultural plane.

We thank you for your patience in reading this letter, for your valuable efforts, and for your participation in defending the heritage of the People of the House—the Ark of Salvation and the eye of life.

We ask for your prayers for success in the service of the religion.

— Nabīl, Beirut

According to Wahid, ‘Nabil’ is the Beirut-based Shiʿi academic Nabil Hamed. I could find nothing about this individual online, and I tried the email address on the jpeg of the ‘fatwā’ with no avail.

Thus the ruling on this information itself is that they are “weak chains and are not to be considered authentic”. So despite how it is played by Wahid, this is no Islamic endorsement for entheogens. Wahid states that“this ruling by Grand Ayatollah Rohani I personally find to be quite historically momentous and with its significance wide ranging, offering quite positive future ramifications beyond even the world of Shi’i Muslims…. The equivalent to Grand Ayatollah Rohani’s ruling in an analogous Western context would be for the Vatican to make a similar finding for Roman Catholics. Indeed this is how big this is, and so, as a singular development, it should not be taken lightly or underestimated by anyone.” (Wahid Azal):

Furthermore, while Western governments and legal establishments continue to grapple with some of the most rudimentary issues surrounding legalization (which should optimally be outright decriminalization) of marijuana; and while churches, individuals and groups who use Ayahuasca, Haoma, mushrooms, DMT, Ibogaine, LSD or cannabis in a sacramental and traditional (holisitic) medicinal setting continue to be persecuted by governments and legal establishments in the West with their sometimes utterly ridiculous, draconian scheduling regimes; and while the so-called ‘war on drugs’ (which is literally the ‘war on plants’) rages on in the West, depleting everyone’s resources in the process, whilst ignorantly lumping everyone into the same camp and unjustly victimizing many innocents for no ostensible purpose; one of the highest religious and legal authorities in Twelver Shi’i Islam in Iran has positively weighed in on the debate, made all the correct distinctions between ‘drugs’ and ‘psychoactive substances/entheogens’ in the process (not to mention the distinction between trippers and those who approach these plants as sacraments), and thus made a learned decision and offered a legal ruling affirmatively on our side.

As far as I am concerned, this fatwā changes the whole configuration and contours of the global debate about entheogens and religious freedom and directs it into a much more fertile, nuanced and positive direction from this point forward. If some people in the West may find this positive jurisprudential ruling by a major Iranian Shi’i Muslim cleric problematic to their attempted lobbying of their own authorities in the West; as if this instance would somehow hurt or otherwise discredit their own cause because it is coming from an Islamic source in Iran; then they need to seriously examine their own personal and cultural motivations (not to mention, biases) on the question, because the complex implications of this decision produces nothing but good for the long term best interests of the whole cause.

Why do I say this? Well, for starters, show me one preeminent religious or even a secular political figure anywhere else in the world recently that has done anything remotely similar to this? The Spirit does indeed work in mysterious ways, and the whole plant community worldwide needs to take this on board now, thereby making of this specific instance a precedent everyone can rally around, because a powerful ally has emerged from the most unlikeliest of quarters: the seat of ecclesiastical Twelver Shi’i Islamic religious learning and power in Qom, Iran. The hand of the Madre, which for us Shi’i Muslims is none other than Fāṭima Zahrā’ herself (viz. the daughter of the Prophet Muḥammad whom we venerate as a divine, cosmic force), is evidently at work here. (Wahid Azal)

Does the fatwā really have that kind of impact or any effect outside of what Wahid has been able to generate from it though? There was no official release of the fatwā in Iran, it does not appear on any Shia ruling website, it received no press in the Iranian media. Virtually, all these substances remain under strict prohibition in Iran. Moreover, historically, Islamic law has been down this road before, with cannabis. This is indicated in the fatwā ruling against cannabis, which likewise was argued as permitted for centuries due to no explicit reference to prohibiting it in the Koran where it is now prohibited on the grounds of “stupefaction through a state of intoxication”. Early Islamic commentators “never failed to remark on the fact that hashish is not mentioned in the Qur’an or the old Prophetic traditions, nor were they able to find any express reference to it in the name of the four legal schools” (Rosenthal, 1971).

While there are a number of local differences, the use of cannabis with a varying intensity has had a time-honoured role in many Muslim countries. This is in contrast to the use of alcohol which, from the religious point of view, became the prime forbidden intoxicant…. There are many reports… that hashish was also used in medical preparations… [It has been] suggested that the interpretation of the Quranic law on intoxicants might have been more tolerant towards the use of drugs such as opium and hashish because of the paucity of means of relieving pain in the medieval Muslim world. (Palgi, 1975)

As noted in an article on collectiveijtihad.org’s article, ‘Is it permissible to use cannabis for recreational or medical reasons?’:

It is found that during the time of the Prophet and Imams, apart from alcohol, other intoxicating substances, including opium, were easily accessible. In spite of this, there are no specific narrations that indicate on their permissibility or impermissibility per se. Rather, narrations from the Prophet and Imams only explicitly prohibit wine.

3. However, there are some general narrations that apparently prohibit every intoxicant substance. For instance:

“The Prophet stated: “Every intoxicant is wine (khamr) and (therefore) every intoxicant is impermissible (ḥarām).

The Prophet stated: “What intoxicates in large amounts, a small amount of it is (also) unlawful”

Some jurists use these narrations to infer the impermissibility of all intoxicants, including cannabis. However…, this line of argument is problematic, because it can be argued that what is prohibited by these traditions is not all types of intoxicants, but only a specific type of it that is in common between wine and similar alcoholic drinks. Therefore, there is no clear/explicit scriptural prohibition of cannabis from the Qurʾān or Sunna.

Therefore, in the absence of any general or specific reason for the prohibition, the juristic maxim (qāʿidat al-fiqhiyya) known as the primacy of permissibility (aṣālat al-ḥill) that is derived from the Qurʾān and the traditions of the Prophet and the Imams is applicable to the case at hand. In accordance with this juristic maxim everything is deemed as being (ḥalāl) unless proven otherwise.

4. Although, there is no explicit prohibition of using cannabis, there is a juristic maxim known as nafī al-ḍarar (‘eliminating harm’). In accordance with this maxim, causing any severe harm to oneself or any harm to others is prohibited. This maxim is derived from the Qurʾān and Sunna. The Qurʾān mentions:

“And do not throw yourselves into destruction by your own hands. And do good; indeed, Allah loves the doers of good.”

In accordance with the unrestricted apparent indication of this verse, an individual is encouraged to avoid actions that bring sever harm or destruction upon themselves. Similarly, the prohibition of causing sever harm or self-destruction can also be found in the narrations of the Prophet and Imams.

The debate among Islamic scholars at the time wether hashish use was permissible, is directly related to the Rohani’s ‘psychedelic fatwā’. In the well researched article ‘Islam and cannabis: Legalisation and religious debate in Iran‘, written by Iranian academics, who consulted with Iran’s leading Shi’a authorities, the maraje’-e taqlid, ‘source of emulation’, we get some idea of the Islamic debate about wether cannabis was halal (meaning “permissible”) a term that encompasses everything that is allowed under Islamic law, or haram -‘forbidden’. or proscribed by Islamic law.

. While the prohibition of wine is an agreed matter based on the explicit Koranic forbiddance, references to hashish, cannabis and other hemp derivatives are absent from the sacred text. This void opens up the possibility of interpretation among legal scholars with results that are not always unanimous…

The lack of Koranic reference stimulated the mind of religious scholars in interpreting the status of cannabis. Given the void in the hermeneutical sources, scholars judged the validity (halal) or prohibition (haram) of cannabis use based analogy (qiyas). Wine (al-khamr) is the comparative element taken into account, but most scholars disagree on equating wine with cannabis. A widely accepted account (hadith-e hil) says, ‘Everything is allowed for you [halal lak] until you learn it is forbidden…’. Hence, cannabis does not carry a total prohibition among most Muslim scholars (Safian, 2013). Allameh Helli (1250–1325), a leading scholar, said, ‘for the poison that derives from the herbs [hashish-ha] and the plants, if it has benefits [manfe’at], its sale and trade is not an issue. If it does not have benefits, then it is not permitted’ (Rezapourshokuhi, 2002). - (Ghiabi, Maarefvand, Bahari, Alavi, 2018)

In fact, cannabis, remained legal in Iran up until 1959 due to this situation, and the legal ruling against it came from International pressure more than anything:

It is with the establishment of the modern state (1920s) and, especially, with the foundation of the Islamic Republic in 1979 that prohibition of drugs, including cannabis, become more stringent… This prohibitionist impetus coincided with the international effort, sponsored by the United States, to control (and later eradicate) opium culture (Musto, 1999). This new vision was eagerly espoused by Iranian lawmakers with the hope of demonstrating their conformism with Western modernity… Cannabis was not included in Iran’s first drug laws and its control remained mostly a question of moral condemnation led by public intellectuals and religious zealots.Despite pressures from the international drug control machinery, which had adopted measures to supervise and control cannabis, the Iranian government ignored the matter (Bouquet, 1950). Only on June 22, 1959, Iran’s Senate approved the first law that made cannabis illegal. (Ghiabi, Maarefvand, Bahari, Alavi, 2018)

It should also be noted here that ‘Islam and cannabis: Legalisation and religious debate in Iran‘ is much closer to an actual fatwā, than Wahid’s ‘Psychedelic Fatwā, which is seams to be just part of an email chain. In this case published in numerous sources, the 8 answers from the 8 Ayotollah’s on 8 questions regarding the permissibility of cannabis constitutes scholarly views that could influence policy or future fatwās, but the document itself is not one. The document presents estefta’āt (formal questions) sent to Shi’a maraje’-e taqlid. As with the alleged ‘Psychedelic fatwā they were not issued as a standalone ruling for the Muslim community, but clearly hold more weight than a privately sent email answering a question.

For more on the Koranic discussion on wine, hashish and the law, see Hashīsh – Intoxicating or Just Corruptive? A 13th Century Jurist’s Distinctions (2018) by Sheza Alqera Atiq, Hashish in Sufism Is Dismissed As Illegal and Degeneration of Islamic Ideals (2018) by Hammad Khan, Is it permissible to use cannabis for recreational or medical reasons? (Collective Johad, 2023) which are particularly relevant to any discussion regarding any alleged fatwā and psychedelics in the Islamic world.

The case in both situations, cannabis and psychedelics, is based purely on their omission in the Koran. This is stated explicitly in the alleged fatwā “for the default principle with plants—as with all other things for which there is no specific revealed text—is permissibility”. As the website collectiveijtihad.org has stated of such rulings.

Therefore, in the absence of any general or specific reason for the prohibition, the juristic maxim (qāʿidat al-fiqhiyya) known as the primacy of permissibility (aṣālat al-ḥill) that is derived from the Qurʾān and the traditions of the Prophet and the Imams is applicable to the case at hand. In accordance with this juristic maxim everything is deemed as being (ḥalāl) unless proven otherwise.

But as noted in the Psychedelic Fatwā, cannabis is now prohibited due to it holding a form of intoxication, and the concept of nafī al-ḍarar (‘eliminating harm’). In that regard, consider the fatwā’s ruling on the “reports” on psychedelics as “weak chains and are not to be considered authentic”, and how the effects of the Amazonian Tea might be perceived by an Iranian cleric witnessing someone under the influence of ayahuasca, and how they might view their claims of visions….

I can not see Iranian orthodoxy, witnessing a person in the midst of ayahuasca induced ecstasy, vomiting out both ends, rolling on the ground, making guttural noises etc., as anything but ‘intoxication’, nor their visionary experiences, if outside the realm of Islamic belief, as acceptable.

Much Ado About Nothing

The Psychedelic fatwā would hold up to scrutiny even less than rulings permitting cannabis did. Cannabis had already held a long established role in Islamic medicine, which psychedelics do not have. To maintain after the initial ruling of permissibility the view would have to be there was no ‘intoxication’ or potential ‘harm’ from psychedelics.

The Reality Sandwich article says the ‘fatwā ‘Shows: “The use of entheogens and psychoactive substances is licit (ḥalāl) for Shiʿi Muslims provided it be under the direction and supervision of qualified experts (ahl al-ikhtiṣāṣ), and that such plant substances as a rule do not impair the mind.” But the ‘fatwā ‘ makes no mention regarding the “supervision of qualified experts” nor does it state that “substances as a rule do not impair the mind”. Moreover, in regards to the submitted reports on their effect, the ‘fatwā’ states “when examined all of them have weak chains and are not to be considered authentic”. The Ruling is based on “One cannot judge something to be forbidden unless there is an explicit text to that effect, or unless it clearly falls under the application of a general prohibition”, and Iranian society having so little knowledge of these various ‘substances’ (no specifics are addressed) its purely on omission alone, and would certainly not stand the test of use in Iranian culture. That is why Wahid is pursuing his interests there, in the somewhat more tolerant climate of Western Cultures.

No publicly documented arrests exist specifically for ayahuasca in Iran, as Ayahuasca is virtually unknown inside there; the brew must be imported or home-brewed from rare Amazonian plants. Iran’s 4,000+ annual drug executions and 80 % of police resources target opium, heroin, meth and cannabis from Afghanistan. Psychedelics fall under the same statutes, so any discovered ayahuasca would be prosecuted as “industrial narcotics,” but none have surfaced in court records or media. Bringing, brewing or drinking ayahuasca in Iran is illegal and carries the same risks as smuggling DMT. The alleged 2014 fatwā offers zero legal protection. Zero confirmed arrests reflect rarity, not tolerance—if discovered, you would face the full weight of Iran’s anti-narcotics machinery.

The Sole Primary Source for the fatwā is N. Wahid Azal (a self-described Sufi mystic living in Australia). He is the only person who has ever posted an image alleged to be the actual email fatwā. He translated it from Persian to English, published it (on his now-deleted blog wahidazal.blogspot.com) and gave all the interviews about it (Reality Sandwich, Psychedelic Times, Alternet, etc.).

No one else—not the Ayatollah’s office, not any other marjaʿ, not any Iranian news outlet—has ever confirmed, quoted, or even mentioned this ruling. The Ayatollah’s own website rohani.ir/fa has never posted it.Grand Ayatollah Rohani had issued numbers of public fatwās on alcohol, opium, and methamphetamines and other drugs, and all got the standard ‘all intoxicants are ḥarām’. Persian-language Google, Aparat, Telegram, or Iranian forums turn up zero hits for “فتوى روحانى مخدرات نفسية” (Religious fatwā on psychoactive drugs) or similar. I had Grok search every fatwā archive in Arabic and Persian for the words مخدر, دیامتی, آیاهواسکا, قارچ جادویی, نباتات مسمومه, etc. (’Magic mushrooms, poisonous plants’ and ‘Narcotics, DMT, Ayahuasca’) → 0 hits. No Iranian cleric has ever cited it. Even pro-psychedelic Shia forums (ShiaChat, r/shia) treat it as ‘that thing Wahid Azal says’. If the psychedelic fatwā ever existed, it was never published officially, so it binds no one—not even the original questioner—under normal marjaʿiyyah rules.

Grand Ayatollahs publish every estaftāʾ (question) and jawāb (answer) they issue. A ruling this explosive would be in the “masāʾil jadīda” (new issues) section. It isn’t.

Rouhani died in 2022; his office never once confirmed it. After his passing, the bureau in Qom re-issued hundreds of old rulings. Journalists, researchers, and even Iranian drug-policy NGOs asked for the psychedelics fatwā.→ Silence. If it were relevant religious jurisprudence, the office would proudly display it to defend the late marjaʿ. Rouhani’s office explicitly told an Iranian researcher in 2019: “لا يوجد فتوى بهذا الخصوص” – “There is no fatwā on this matter.”

Most discussions on the ‘Psychedelic fatwā’ are to be found in English-language media related to psychedelic culture, and these mention the fatwā in the context of Azal’s advocacy or his specific interpretation. Any foreign language article I could find, listed Wahid Azal as the source. Therefore, there is a lack of widely accessible evidence that is entirely independent of Wahid Azal’s initial dissemination of the information.

Comparatively, the Iranian document Islam and cannabis: Legalisation and religious debate in Iran, prepared for legal discussion in Iran, by 4 Iranian academics, and submitted to the engagement of 8 Ayatolllahs from Iran’s leading Shi’a authorities, the maraje’-e taqlid, ‘source of emulation’, can be found on multiple academic and legal sites, both here, and in Iran.

The Bottom Line is: Wahid Azal is the beginning, middle, and end of the story. Every blog post, Reddit thread, and Vice-style article is just an echo of his 2014 interviews. Until the Ayatollah’s office uploads the actual Arabic/Persian text, the “Shia psychedelics fatwā” holds little relevance.

What the fatwā did do however, wether relevant or not in Iran, is, it gave a boost of confidence to many advocates of psychedelic drugs in the West, as can be seen by the numerous articles, where Wahid’s interpretation of it has been accepted without question.

News stories and internet chatter on fatwā

Here are some examples of the hype the alleged fatwā generated

‘Psychedelics Now Halal In Islam’

It is encouraging to see this move coming from the exoteric manifestation of one the largest religions of the current world. It only makes sense for the others to follow suit for such mystical experiences and revelations similar to the ones psychedelics can engender are seem to be at the source of all religions.

‘Iranian religious authority considers psychedelic medicines Halāl’

In mid-March 2014, Sayyed Mohammad Sadeq Hussaini Rohani, who is a Grand Ayatollah (meaning the highest authority on Shi’ite Islam—basically, the equivalent of the Pope), announced that entheogenic drugs are permissible (ḥalāl) for Muslims under traditional Islamic law. That means, that so long as psychedelics are taken under the observation of a trained specialist, it’s not sinful or forbidden (haram).

Grand Ayatollah Rohani could have been open to mind-altering drugs because the psychedelics have a resemblance to Esfand, also known as Syrian rue (peganum harmala), which contains the psychoactive indole alkaloid harmaline, a central nervous system stimulant and MAO inhibitor used for thousands of years in the region. According to at least one Shi’i tradition, the Prophet Mohammed took esfand for 50 days.

Whatever the precise theological reasoning behind the Rohani’s fatwa, with it, Iran could leapfrog Western nations when it comes to psychedelic research. Although psychedelics are seeing a research renaissance in the West, research here is limited by their criminalized legal status, as well as lack of funding. But the Islamic Republic has cleared the way. Phillip Smith, 2017

The alleged fatwā also brought the topic of ‘psychedelics’ and ‘permissibility’ to Shia and Islamic discussion forums: The Islamic Board page ran ‘Help! Very Confused About the Islamic Ruling On Cannabis & Psychedelic Use!’; The Shia Chat forum had discussions like ‘The medical use of psychoactive substances and fatwas’ and ‘Psychedelics (LSD, DMT etc.) persmissibility’

Conclusions on the ‘Psychedelic fatwā’

My view is, the statement from Ayatollah Rohani is not a forgery, but it is also in no way an official fatwā. It was never released publicly in Iran, and just constitutes a private email correspondence, which notes that there is no specific prohibition of the substances in question in the Koran, still a fatwā, but of little identifiable impact outside Wahid’s hype. It is in no way a Shia endorsement of the entheogenic path. The text, sourced solely from Wahid Azal, applies the standard Shia principle of default permissibility (aṣālat al-ibāḥa): unnamed plants are ḥalāl unless explicitly prohibited by Koran/Hadith or causing intoxication (Sekr) and loss of intellect, as with hashish. It dismisses submitted reports (scientific, visionary, or hadith-based) as having “weak chains” and offers no endorsement of therapeutic, spiritual, or supervised use. No mention appears of “expert guidance (ahl al-ikhtisāṣ)”, “mind non-impairment”, or entheogenic benefits—these are extrapolations. Rohani’s office, official websites, and archives contain no trace of it; a 2019 query yielded “There is no fatwa on this matter.” In Iran, it has zero impact: psychedelics remain Schedule I narcotics, and the ruling binds no one under taqlid rules.

Beyond the hype around the alleged fatwā, the stories generated by it propelled Wahid Azal into the growing psychedelic movement, as an expert on both psychedelics and Iranian mysticism. I have corresponded and interacted with Wahid Azal, and I would suggest he is well aware of this standing on his fatwā presented here.

Wahid is one of the most knowledgable and well read figures on the subject of Islamic and Eastern mysticism and magic that I have personally interacted with. However, on the flip side of that, he has a long history of online feuds, doxxing accusations, and claiming secret initiations into multiple esoteric orders. As we shall see Wahid Azal can be a nasty and aggressive Internet troll, who has literally terrorized members of the Baha’i and Ahmadi Religion of Peace & Light (AROPL) often threatens to sue people or turn them into various authorities. He has also had people platforms shut down, videos removed, etc. A lot of this conflict seems to stem from people’s rejection of Wahid’s messianic like claims of divinity…. In part 2 of this article, The Strange Case of Wahid Azal, we will take a closer look at the man who named himself ‘Wahid Azal’ and some of the fascinating controversies that have followed him around.